Abstract

A simple, cost-effective yet rapid and sensitive sensor for on-site and real-time Hg2+ detection based on bovine serum albumin functionalized fluorescent gold nanoparticles as novel and environmentally friendly fluorescent probes was developed. Using this probe, aqueous Hg2+ can be detected at 0.1 nM in a facile way based on fluorescence quenching. This probe was also applied to determine the Hg2+ in the lake samples, and the results demonstrate low interference and high sensitivity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Among heavy metal ions, mercury is considered highly toxic and widespread pollutant, and its damage to the brain, nervous system, endocrine system and even the kidneys is well known [1]. Water-soluble divalent mercuric ion (Hg2+) is one of the most usual and stable form of mercury pollution, which provides a pathway for contaminating vast amounts of water and soil. Ionic mercury can be converted into methyl mercury by bacteria in the environment, which enters the food chain and accumulates in higher organisms [2]. Therefore, environmental monitoring of aqueous Hg2+ becomes an increasing demand. Traditional methods such as inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICPMS) to detect mercury ions often are costly, nonportable and require sophisticated instruments for analysis [3]. Thus, the development of new, practical assays for Hg2+ detection remains a challenge. Toward this goal, a number of the sensitive and selective sensors for the detection of Hg2+ have been developed, based on gold nanoparticles [4–7], fluorophores [8–11], DNA or DNAzymes [12–16], polymer materials [17, 18] and proteins [19, 20]. Among these sensors, many are constructed with oligonucleotides containing thymine (T) as the sensing elements. But using nucleic acids or enzyme as sensing element makes it too costly and time-consuming for real life. Moreover, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) standard for the maximum allowable level of inorganic mercury in drinking water is 2 ppb (10 nM) [21]. This concentration is much lower than the detection limit of most available sensors. There is a need for more sensitive, convenient and economic methods to detect Hg2+ in environment.

Recently, highly fluorescent gold nanoparticles were used as probes to detect Hg2+ based on fluorescence quenching through Hg2+-induced aggregation of AuNPs [22]. The limit of detection was 5 nM, which was a lower result than EPA standard, and confirmed that the fluorescent gold nanoparticles were sensitive sensors. And Ying et al. have reported a red-emission high-fluorescent bovine serum albumin (BSA) functionalized gold nanoparticles (BSA-GNPs) by a simple, one-pot, “green” synthetic route [23]. Considering the BSA molecular surface is rich in amino, carboxyl groups that can readily coordinate with heavy metal ions, maybe resulting in the fluorescence quenching of BSA-GNPs, we employed BSA-GNPs to detect Hg2+ by the fluorescence quenching in this work. In addition, a practical environmental assay was carried out.

Experimental Section

Chemicals and Materials

All chemicals used were of analytical grade or of the highest purity available. Chloroauric acid (HAuCl4) was obtained from Sigma–Aldrich (USA) and used as received. BSA was obtained from Genview. The used metal salts Pb(NO3)2, Ni(NO3)2·6H2O, Cd(NO3)·4H2O, FeCl2·4H2O, Mg(NO3)2·6H2O, CaCl2·2H2O, Co(Ac)2·6H2O, Zn(Ac)2·2H2O, BaCl2·2H2O, CuSO4·5H2O, Hg(NO3)2·2H2O, Cr(NO3)3·9H2O, Mn(Ac)2·4H2O and NaOH were purchased from Beijing Chemical Reagent Company (Beijing, China). The stock solution of Hg2+ was 5 mM. All glassware was thoroughly cleaned with freshly prepared 3:1 HCl/HNO3 (aqua regia) and rinsed thoroughly with Mill-Q (18 MΩ cm−1 resistance) water prior to use.

Instrumentation

The fluorescence spectra were measured using a Cary Eclipse Fluorescence spectrophotometer (USA Varian). Both the excitation and emission slit widths were set to 20 nm, and the measurement was done at 20°C. The excited wavelength was 470 nm.

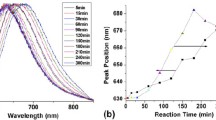

Preparation of BSA-GNPs

BSA-GNPs were fabricated by a previously reported method [23]. In a typical synthesis, aqueous HAuCl4 solution (5 mL, 10 mM, 37°C) was added to BSA solution (5 mL, 50 mg/mL, 37°C) under vigorous stirring. Two minutes later, NaOH solution (0.5 mL, 1 M) was introduced, and the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 12 h. The color of the solution changed from light yellow to light brown, and then to deep brown. The deep brown solution of BSA-GNPs emits an intense red fluorescence (Fig. 1b (a), under UV light 365 nm). The changes of fluorescence intensity of BSA-GNPs at various reaction times were showed in Fig. S1. The fluorescent BSA-GNPs show emission peak at 640 nm, excitated by 470 nm (Fig. 1b (a)).

Procedures for Hg2+ Detection

The as-prepared BSA-GNPs were diluted to 40 times, the resulting BSA-GNPs solution was used as the detection probe. The samples were added into the BSA-GNPs probe with a volume ratio (V/V) 4:1, which was the mixture of the 400 μL Hg2+ solution and 100 μL BSA-GNPs probe. In the experiments of sensitivity of the detection, the solution of Hg2+ was prepared from 0.1 nM to 4 μM. To confirm the practical application of the probes, a water sample from a lake was filtered through a 0.2-μm membrane. A 100 μL of 100 μM Hg2+ solution was added into 900 μL lake water, the resulting solution was 10 μM, which was further diluted a series of different concentrations of samples with lake water.

Result and Discussion

Fluorescent Detection of Hg2+

The overall detection strategy is shown in Fig. 1a. BSA is a large globular protein with a good essential amino acid profile and bear fluorescence emission groups (tryptophan, tyrosine and phenylalanine). So, there are lots of amino acid residues on the surfaces of BSA-GNPs, which can be proved by the FTIR spectra (Fig. S2) [24].

To evaluate the attachment of BSA onto the surface of Au, the FTIR spectra of BSA and BSA-GNPs were shown in Fig. S2. Compared to the spectrum of pure BSA, the characteristic peaks of BSA-GNPs such as at 1,654, 2,958 and 3,421 cm−1 can be clearly seen, which indicating the modification of BSA on the Au nanoparticles. Compared with the spectrum of pure BSA (Fig. S2a), the characteristic peaks of BSA-GNPs such as at 1,654, 1,546 cm−1 can be clearly seen (Fig. S2b), which are attributed to the amide I and amide II vibrations of BSA on the Au nanoparticles [24, 25]. The FTIR spectra indicated that the basic structure of BSA still maintained after modified the gold nanoparticles. In addition, the residues of amino acid can readily coordinate with heavy metal ions [26, 27], when Hg2+ coordinated with the BSA-GNPs, the fluorescence emission of BSA-GNPs may be quenched.

The fluorescence emission of the BSA-GNPs was shown in Fig. 1b; the maximum emission and excitation wavelengths were at 640 and 470 nm, respectively. The fluorescence emission was readily quenched in the presence of Hg2+. As illustrated in Fig. 1b, the BSA-GNPs solution showed strong emission at 640 nm (curve a), when added the solution of 4 μM Hg2+ (curve b), the fluorescence emission was quenched immediately. The inset is the corresponding photograph, the BSA-GNPs solution showed strong red emission under UV light and the red emission of BSA-GNP-probes was quenched by the addition of Hg2+. The corresponding TEM images of original and the aggregated BSA-GNPs were shown in Fig. S3. After the addition of Hg2+, the dispersed BSA-GNPs with diameter in ca. 2 nm (Fig. S3a) aggregated seriously (Fig. S3b). Therefore, Hg2+ detection could be easily realized via monitoring the fluorescence quenching of the BSA-GNPs under the UV light.

To evaluate the detectable minimum concentration of Hg2+ in aqueous solution by fluorescence quenching, the various concentrations of 0.1 nM–4 μM Hg2+ were added into BSA-GNPs solution, respectively. As shown in Fig. 2, all the maximum fluorescence emissions of the BSA-GNPs were at about 640 nm, and the fluorescence intensity of the BSA-GNPs showed a gradual decrease with the concentration of Hg2+ increasing from 0.1 nM to 4 μM. Notely, the fluorescence was quenched completely at about 4 μM. However, the red emission of BSA-GNPs can not be observed after added into 2.5 μM Hg2+ under the UV light. The inset is a linear between the fluorescence intensity with the different concentrations of Hg2+. There is a well linear relationship over the concentration range from 1 nM to 4 μM with the R2 = 0.98876, indicating the ultrasensitive detection of Hg2+. The detection limit of the BSA-GNPs probe for Hg2+ detection was 0.1 nM, which was much lower than the EPA standard for the maximum allowable level 2 ppb (10 nM) in drinking water. To confirm the rapid response of BSA-GNPs to Hg2+, we measured the response time of fluorescence quenching by monitoring the fluorescence changes for 5 min after the addition of Hg2+ into the BSA-GNPs (Fig. S4). As a result, the fluorescence quenching by Hg2+ was completed almost within 1 min, allowing the rapid detection of Hg2+. The experimental results indicate the feasibility of detecting Hg2+ accurately using the BSA-GNPs probes.

Selectivity of the Sensing System

We investigated the selectivity of our new approach for Hg2+ over other metal ions (500 μM Cd2+, Cr3+, Ba2+, Zn2+, Ca2+, Mn2+, Mg2+, Fe2+,Co2+ and 50 μM Ni2+, Cu2+, Pb2+) under the same conditions. As indicated in Fig. 3a, the solution of BSA-GNPs after added other ions has fluorescence emissions at about 640–650 nm. Importantly, the fluorescence of the BSA-GNPs was quenched completely in the presence of Hg2+, while almost 100% fluorescence quenching was not observed in the presence of other metal ions. All of the fluorescence intensities of BSA-GNPs after the addition of other ions were much higher than that of Hg2+, although the concentration of other ions was 10–100 times more higher than that of Hg2+ solution, indicating the BSA-GNPs probe was highly selective for Hg2+ over the other metal ions. To further illustrate the selectivity of this BSA-GNPs-based detection system, we used the enhanced ratio to express the intensity ratio, that is, the value of intensity of ion/intensity of control (I/I0). In the Fig. 3b, the ratio of intensity of fluorescence spectra I/I0 (640 nm) can be observed clearly. For example, the I/I0 value of Cd2+ (500 μM) was at least 10 times higher than that of Hg2+ (4 μM), suggesting the detection limit for Hg2+ was almost 100 times higher than Cd2+. And the solutions of 50 μM Ni2+, Cu2+, Pb2+ were over 10 times higher than Hg2+. By comparison, the decrease in fluorescence intensity was more remarkable in presence of Hg2+. The addition of other ions with high concentrations to the BSA-GNPs has some effect on the intensity of fluorescent spectra, but did not occur fluorescence quenching completely. Additionally, we also investigated the red emission of BSA-GNPs added with all the ions under UV light. The BSA-GNP probes were added 50 μM of Cd2+, Cr3+, Ba2+, Zn2+, Ca2+, Mn2+, Mg2+, Fe2+, Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, Pb2+ and 4 μM Hg2+, respectively. As shown in Fig. 3c, the red emission of BSA-GNPs was quenched completely in presence of Hg2+; however, the red emissions of BSA-GNPs upon addition of other ions were observed clearly. The experimental results indicate that only the addition of Hg2+ caused fluorescence quenching completely, revealing the exceptional specificity of this present method.

a Fluorescence spectra of solutions of 100 μL BSA-GNPs on addition of 400 μL other ions (500 μM Cd2+, Cr3+, Ba2+, Zn2+, Ca2+, Mn2+, Mg2+, Fe2+, Co2+, 50 μM Ni2+, Cu2+, Pb2+ and 4 μM Hg2+. b Enhanced ratios (I/I0) of the fluorescence intensity (640 nm) of solution in (a). Excitation wavelength: 470 nm. c Fluorescence photographs of 100 μL BSA-GNPs upon addition of 400 μL of other ions other ions (50 μM) and Hg2+ (4 μM)

To further evaluate the selectivity, the Hg2+ detection in the presence of other metal ions was investigated. The fluorescence responses of BSA-GNPs to different concentrations of Hg2+ in mixture solutions were obtained in Fig. S5. The results indicated that the fluorescent intensity of BSA-GNPs still showed a gradual decrease with the concentration of Hg2+ increasing coexisting with other metal ions in solution 1. Compared with mixture solution 1 (Fig. S5a), the fluorescent intensity of BSA-GNPs decreased a lot coexisting with Cu2+, Pb2+ and Ni2+ (Fig. S5b), but it did not affect the detection of Hg2+. Though other metal ions coexisted, the experimental results show that Hg2+ can be detected against other heavy metals.

Application

To demonstrate the potential practical application of the assay to measure the Hg2+ content in lake water, a water sample from a freshwater lake on our campus was collected and filtered through a 0.2-μm membrane and then analyzed by ICPMS (Table S1). We did not detect the presence of Hg2+ ions in the lake water samples, which was in good agreement with ICP-MS data. To determine the concentration of Hg2+, we applied a standard addition method [8, 9, 13, 28, 29]. The intensity of fluorescence spectra of the samples was decreased with the increase of Hg2+ concentrations from 0.1 nM to 4 μM. From Fig. 4, it is observed that although the sample may contain some unknown contamination that did not interfere with the BSA-GNPs-based sensing system detecting aqueous Hg2+, these experimental results indicate BSA-GNPs-based sensing system can be utilized for analyzing the practical samples.

Fluorescence response of BSA-GNPs upon addition of Hg2+ prepared using lake water. All other conditions were the same as those described in Fig. 2

Conclusion

In summary, a simple, portable detection method based on fluorescent BSA-GNPs probe that allows rapid, on-site, real-time detection of Hg2+ has been developed. The method would also address many of the challenges of the instrument-intensive methods of analysis. The experimental results show that Hg2+ can be detected quickly and accurately with very low detection limit (0.1 nM) and excellent discrimination against other heavy metals. We believe this method may act as a platform for the rapid detection of Hg2+ in aqueous biological and environmental samples with high selectivity and sensitivity.

Electronic supplementary material

(See supplementary material 1)

References

Nolan EM, Lippard SJ: Chem. Rev.. 2008, 108: 3443. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD1cXovFygurY%3D] 10.1021/cr068000q

Harris HH, Pickering IJ, George GN: Science. 2003, 301: 1203. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD3sXmvFejurs%3D] 10.1126/science.1085941

Li Y, Chen C, Li B, Sun J, Wang J, Gao Y, Zhao Y, Chai Z: J. Anal. At. Spectrom.. 2006, 21: 94. 10.1039/b511367a

Darbha GK, Singh AK, Rai US, Yu E, Yu HT, Ray PC: J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2008, 130: 8038. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD1cXms1GitbY%3D] 10.1021/ja801412b

Darbha GK, Ray A, Ray PC: Acs. Nano.. 2007, 1: 208. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2sXht1ars7fF] 10.1021/nn7001954

Chai F, Wang CG, Wang TT, Ma ZF, Su ZM: Nanotechnology. 2010, 21: 025501. Bibcode number [2010Nanot..21b5501C] Bibcode number [2010Nanot..21b5501C] 10.1088/0957-4484/21/2/025501

Yu CJ, Tseng WL: Langmuir. 2008, 24: 12717. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD1cXht1WlsbnI] 10.1021/la802105b

Chiang CK, Huang CC, Liu CW, Chang HT: Anal. Chem.. 2008, 80: 3716. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD1cXlslOisrs%3D] 10.1021/ac800142k

Liu CW, Huang CC, Chang HT: Langmuir. 2008, 24: 8346. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD1cXnslOgtr0%3D] 10.1021/la800589m

Wang H, Wang YX, Yang RH: Anal. Chem.. 2008, 80: 9021. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD1cXhtlWqu7vF] 10.1021/ac801382k

Bhalla V, Tejpal R, Kumar M, Sethi A: Inorg. Chem.. 2009, 48: 11677. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD1MXhtlChtbjE] 10.1021/ic9016933

Lee JS, Han MS, Mirkin CA: Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.. 2007, 46: 4093. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2sXmtlOlt70%3D] 10.1002/anie.200700269

Li T, Dong SJ, Wang EK: Anal. Chem.. 2009, 81: 2144. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD1MXitVOms7g%3D] 10.1021/ac900188y

Lee JS, Mirkin CA: Anal. Chem.. 2008, 80: 6805. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD1cXptVyrsL0%3D] 10.1021/ac801046a

Ye BC, Yin BC: Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.. 2008, 47: 8386. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD1cXhtlKlsr%2FM] 10.1002/anie.200803069

Guo WW, Yuan JP, Wang EK: Chem. Commun.. 2009, 23: 3395. 10.1039/b821518a

Liu XF, Tang YL, Wang LH, Zhang J, Song SP, Fan C, Wang S: Adv. Mater.. 2007, 19: 1471. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2sXmvVamsb0%3D] 10.1002/adma.200602578

Zhao Y, Zhong Z: J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2006, 128: 9988. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD28XmvFejsLk%3D] 10.1021/ja062001i

Chen P, He C: J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2004, 126: 728. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2cXjt1Cg] 10.1021/ja0383975

Wegner SV, Okesli A, Chen P, He C: J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2007, 129: 3474. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2sXisVajtLY%3D] 10.1021/ja068342d

Mercury Update: Impact on Fish Advisories; EPA Fact Sheet EPA-823-F-01–001; Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Water: Washington, DC, 2001.U.S. EPA Mercury Update: Impact on Fish Advisories; EPA Fact Sheet EPA-823-F-01-001; Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Water: Washington, DC, 2001.U.S. EPA

Huang CC, Yang ZS, Lee KH, Chang HT: Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.. 2007, 46: 6824. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2sXhtFamt7bP] 10.1002/anie.200700803

Xie JP, Zheng YG, Ying JY: J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2009, 131: 888. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD1MXktVynsQ%3D%3D] 10.1021/ja806804u

Retnakumari A, Setua S, Menon D, Ravindran P, Muhammed H, Pradeep T, Nair S, Koyakutty M: Nanotechnology. 2010, 21: 055103. Bibcode number [2010Nanot..21e5103R] Bibcode number [2010Nanot..21e5103R] 10.1088/0957-4484/21/5/055103

Mohapatra S, Mallick SK, Maiti TK, Ghosh SK, Pramanik P: Nanotechnology. 2007, 18: 385102. Bibcode number [2007Nanot..18L5102M] Bibcode number [2007Nanot..18L5102M] 10.1088/0957-4484/18/38/385102

Shao N, Jin JY, Cheung SM, Yang RH, Chan WH, Mo T: Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.. 2006, 45: 4944. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD28XnvVejurc%3D] 10.1002/anie.200600112

Slocik JM, Zabinski JS, Phillips DM, Naik RR: Small. 2008, 4: 548. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD1cXmvFWlt7Y%3D] 10.1002/smll.200700920

Huang CC, Chang HT: Anal. Chem.. 2006, 78: 8332. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD28XhtFynurzK] 10.1021/ac061487i

Liu CW, Huang CC, Chang HT: Anal. Chem.. 2009, 81: 2383. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD1MXhvFSmsb8%3D] 10.1021/ac8022185

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the National High-tech Research and Development Program of China (863 Program 2007AA03Z354), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project No. 20703009, 20971020).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Chai, F., Wang, T., Li, L. et al. Fluorescent Gold Nanoprobes for the Sensitive and Selective Detection for Hg2+. Nanoscale Res Lett 5, 1856 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11671-010-9730-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11671-010-9730-y